Military Relief Models

by Mapa Scotland co-founder Roger Kelly

This article gives an account of the extensive use of military relief models before the Second World War and their role in the Normandy Campaign of 1944. It goes on to relate Jan Tomasik’s novel idea for a landscape map at Black Barony and its creation in the 1970s. It ends with developments since the map’s construction.

Map Models

Colin McVean Gubbins was a grandson of the Penicuik papermaking family, the Cowans, and grew up at the kilted knee of his grandfather Colin McVean who’d supervised the Japanese Empire’s first geographic surveys from 1869 onwards. His uncle Dondo McVean had served in the Himalayas with Rattray’s Sikhs and had been Winston Churchill’s tentmate in the Malakand Field Force. Bold, practical and far-thinking, Gubbins acted as British military liaison with Polish Forces, first in Poland at the time of the German invasion in 1939, and then in France and in the operations to defend Norway in 1940. In the summer of 1940 he was given the task of preparing the Home Front against invasion, finding places for exiled army, navy and air force personnel, and making plans for deploying irregular forces all over the home territory for an eventual last-ditch defence of Britain. Later in the war, Gubbins, as Head of the Special Operations Executive, was to develop his ideas from this time, co-ordinating clandestine operations behind enemy lines in Occupied Europe.

The Second World War saw the extensive use of increasingly sophisticated terrain models. The models were hand crafted by enlisted sculptors, architects, stage designers and artists using all sorts of basic materials. As Pearson notes, “model-making materials varied according to the specific location. The model makers in Cairo used ‘mangarieh’, a mixture of minced newspaper, local plaster and glue. A photo-skin was created by mosaicing re-scaled photographs of the area and pasting the photo-skin onto the model, using road intersections or other common reference points for registration. The availability and close scrutiny of aerial photography using stereoscopes was an essential part of the more detailed stages in the modelling process. Maps were used for reference to locate airfields, railways and roads before the model was finished. In order to promote realism and provide personnel with portable visual references while conducting operations, the terrain models were sometimes illuminated and then photographed to replicate as closely as possible the light that would exist at the time of the planned operation. Aircrews could thus be briefed with photographs taken from above the model, whereas Commandos would be shown photographs of the model as if viewed from the sea.”

From strategic relief maps produced to a scale of 1:100,000 or 1:500,000, in which the vertical scale was exaggerated, to tactical maps for coastal assault and airborne operations, these maps brought landform to life and were invaluable in all key aspects of military planning and operational responsiveness.

Across Europe there had long been an interest in relief maps and models. The Musée des plans-reliefs in Paris has a collection of about one hundred models – “portraits in relief” – of towns and their surrounding countryside which were used to illustrate the strategic implications of local landform.

Poland’s inter-war mapmaking was of great simplicity and clarity. The Wojskowy Instytut Geograficzny [Military Geographic Institute] or WIG operated in Warsaw from 1921 onwards. The Institute, subordinate to the Ministry of Military Affairs, was given the tasks of making astronomic, geodetic and topographic measurements of the country and preparing precise topographic maps of Poland for printing and publishing. Maps published by WIG were intended for military use, but, because of their clarity and versatility, were more widely used. Mapa Taktyczna Polski 1:100 000 [Tactical Map of Poland 1:100,000] was a map on 482 sheets, of which 437 sheets were made by 1937 with a two-kilometre military grid reference system. Later, during the war, the National Army and the Geographic Section of WIG in exile operated in Edinburgh from 1941. Maps were prepared covering the territory of Poland at 1:100,000.

In Germany, around 1925, Karl Wenschow (1884-1947) developed a procedure for creating shaded relief which now bears his name. A three-dimensional model of the terrain is carved with precision routers from a block of plaster. The model is then obliquely illuminated and photographed from a distance of 40 to 50 metres using a special camera.

Britain already had its own tradition of military relief model making. A 1.5m long physical relief model of the Scottish landscape was used at Barony Castle during the war years. As Alastair Pearson noted, the 1914-18 conflict had seen around a thousand relief models made for British forces. Work on models for the successful Zeebrugge Raid in 1918 had shown the exceptional value of relief models in coastal assault and defence, and in particular heralded their importance for combined operations.

It was exactly this kind of action in support of Commando operations in Norway, in which Gubbins was involved, that led to the formation of a terrain modelling unit under British command as early as the summer of 1940. Soon the most pressing problem was home defence against threats from sea and air. The terrain of Scotland was closely studied to prepare for an imminently expected invasion, thought likely to be launched from German-occupied Norway. Polish forces were deployed to defend a long stretch Scotland’s east coast from Montrose in Angus to Burntisland on the north shore of the Firth of Forth.

Generals Maczek and Montgomery

As a seasoned cavalryman and tank commander with combat experience of the recent German invasions of Poland and France, General Stanisław Maczek of the Polish army-in-exile was a celebrated user of the lie of the land in military strategy and tactics, and contour maps were his stock-in-trade. Edinburgh was a key source of worldwide contour map information and production by firms such as Bartholomew, Nelson and W & A K Johnston. The Polish forces prepared for coastal defence, tried to second guess the invasion strategy and tactics, and moved to take up the most effective positions from which they could respond quickly to an invasion of Scotland’s east coast. They later prepared for the invasion of France in 1944.

In parallel with Polish troop deployments to protect the Scottish coast, Lt.-General Bernard Law Montgomery, who had been highly effective in the defence of Belgium and evacuation of Dunkirk, took over key sections of coastal defence in the south of England: Hampshire and Dorset in July 1940, Kent in April 1941, and a full South Eastern Command overseeing the defence of Kent, Sussex and Surrey in December 1941. During this time Montgomery developed and rehearsed his ideas and trained his soldiers, culminating in Exercise Tiger, May 19-30 1942, a combined forces exercise involving 100,000 troops (not to be confused with SHAEF’s ill-fated Exercise Tiger in 1944).

Montgomery is believed to have visited Peeblesshire during 1942, perhaps to help inaugurate an element of training at the Polish Staff College at Eddleston. His visit presumably took place before preparing for his new tasks in North Africa at El Alamein in August of that year. Maczek’s battle experience in stalling the advance of German tank columns in southern Poland was at that time unique among the Allied commanders and would have been of great interest to Montgomery.

Lieutenant Zbigniew Mieczkowski of General Maczek’s 1st (Polish) Armoured Division attended the Staff College at Barony Castle for training promising officers for higher rank. He has confirmed that Maczek was involved and frequently to be found there, but probably not resident because his duties took him all over Scotland. Maps and mapping were, of course, fundamental to the training.

Naturally, as D-Day approached, Maczek and Montgomery, each concerned with repelling a combined operations coastal invasion in the dark days of 1940 and 1941, would be well suited to plan for the offensive role envisaged for the Allied landings in Europe.

Montgomery returned to Scotland to visit the 1st Armoured Division again in the build up to ‘Operation Overlord’ at the beginning of March 1944 and was much impressed with what he saw of its fighting strength. He used this knowledge to apply pressure on the Polish Commander-in-Chief Sosnkowski who was reluctant to commit reserves to Overlord wholeheartedly. If he could not have Maczek’s Division in full strength, Montgomery threatened that he would not involve the Poles in Normandy at all. A working arrangement was quickly found.

Within a month of the first Normandy landings in June 1944, a million Allied troops had been brought ashore along with vast quantities of war materiel, stores and provisions. To support the Polish forces as they swept through Normandy and the Low Countries, a young Pole, Sergeant Jan S Tomasik, former builder and son of a Kraków circuit judge, was engaged fully in the duties of the quartermasters department and worked closely in liaison with his U.S. and British counterparts.

Tomasik was able to put his experience in procuring supplies and maintaining reserves to good use in business after the war.

1st Armoured Division in Normandy

But first General Maczek was to put his military experience to decisive use after the D-Day landings when the Allies and their Axis foes became locked in a stalemate around the city of Caen.

Taking a commanding position on Hill 262, Maczek’s Polish forces helped prevent the enemy regrouping by bottling up and destroying German fighting units and equipment at the Falaise Gap. By 22 August, all German forces west of the Allied lines were dead or in captivity. Historians differ in their estimates of German losses in the pocket. Most state that between 80,000 and 100,000 troops were caught in the encirclement, of which 10,000–15,000 were killed, 40,000–50,000 taken prisoner and 20,000–50,000 escaped. In the northern sector alone, German material losses included 344 tanks, self-propelled guns and other light armoured vehicles, as well as 2,447 soft-skinned vehicles and 252 guns abandoned or destroyed. In the fighting around Hill 262, German losses totalled 2,000 killed and 5,000 taken prisoner, as well as 55 tanks, 44 guns and 152 other armoured vehicles lost. The once-powerful XXII SS Panzer Division lost 94 per cent of its armour, nearly all its artillery and 70 per cent of its vehicles. Mustering close to 20,000 men and 150 tanks before the Normandy campaign, after Falaise it was reduced to only 300 men and 10 tanks.

(You can see old photographs of the 1st Armoured Division’s progress in Europe on YouTube — note that the end quotation should state “other nations”, not “all nations”)

During the war Danesfield House at Medmenham in Buckinghamshire became the location of Britain’s main secret modelmaking workshops. Here relief map models were produced with the terrain often enhanced with photographic layers. Model makers worked around the clock, seven days a week, in eight or twelve hour shifts. Their work was top secret, highly demanding and tied to tight deadlines.

The Normandy campaign was very carefully planned using an enormous relief model of Normandy and the whole of Northern France which was secretly assembled in London at Montgomery’s old school, St. Paul’s, Hammersmith. After a dry run on April 7 1944 to describe the invasion plan ‘Operation Overlord’ to the senior commanders most closely concerned, a full dress presentation using the relief map was given on May 15 with Eisenhower, Churchill, King George VI, Chiefs of Staff, Corps Commanders and civil servants attending.

Individual rubber models of the separate landing areas for Overlord are known to have been used by troops in the field. Typically, these models showed the details of relief and tide lines, the slope of the beach, positions of buildings, and locations of the anti-landing craft system known as hedgehogs. Surviving models from the period are now treasured exhibits, few having survived.

The appeal of models to the general public was already proving intense. Even before the events in Normandy were unfolding, military models had become a major public attraction across the Atlantic. At the Museum of Modern Art in New York, between January and March 1944, Norman Bel Geddes (father of actress Barbara) and his team displayed their massive War Maneuver Models Exhibition which the audience viewed from raised catwalks and runways. Bel Geddes had already made a name for himself through futuristic city planning presentations and scale models for General Motors and Life magazine, and his war work was to culminate in modelling and filming Tokyo Bay for strategy tactics and training. We know that one relief model was to prove inspirational to Jan S Tomasik: the map of Belgium at the Brussels World Fair of 1958.

Jan Tomasik and Black Barony

After the war, Tomasik – who never lost his quartermaster’s passion for stockpiling foodstuffs and equipment – became a successful hotelier, owning the ever-expanding Learmonth Hotel in Edinburgh’s West End. The hotel bar became a favourite watering hole for Polish veterans in the Edinburgh area, including a neighbour across the road who happened to be Tomasik’s old Commander of the 1st Armoured Division, General Maczek. In his hotel Tomasik was able to offer employment to the General, who, like all Polish servicemen in the West, had no military pension (one was later awarded by the town of Breda in the Netherlands in thanks for its liberation by the Poles enabling him to rent a house in Marchmont). In the early post-war years the General was reported to be serving as a storeman at the Gifford Co-op in East Lothian. Now, in the 1960s, he found himself working as a barman. Tomasik was well known as an ambassador on the tartan tourist scene, visiting the U.S.A. in the kilt, for example, to drum up business. He also maintained close links with the Polish Consulate in Edinburgh and was able to penetrate the ‘Iron Curtain’, visiting Poland regularly to obtain labour and supplies by special permit.

The old staff college at Barony Castle near Eddleston Station was operated as a country hotel for two decades after the war, but the Peebles railway closed as part of the ‘Beeching cuts’ of 1962 and the hotel was put up for sale a few years later. In the autumn of 1968 Jan S. Tomasik bought it as a going concern (it had to operate as a business to fulfil previous commitments). The big old house had powerful associations because of its wartime use by the Poles and the 58-acre estate had ample storage space for Tomasik’s agricultural and equipment needs.

After running for a year under its new owner, the hotel closed for refurbishment in the autumn of 1969, to be re-opened as a hotel and partly as a home for members of Tomasik’s extended family. A new dining room was created and a series of new bathrooms reduced the need for hot water jugs and chamberpots.

Refurbishment continued through 1970 with the installation of a lift and the tidying up of the gardens and woods. By the spring of 1971 the revamped ‘Hotel Black Barony’ reopened for business as part of the Learmonth Hotels group, although work on the third floor was not yet complete. The hotel was managed by Jan Tomasik’s daughter Catherine and her husband Marek Raton. Through the summer the hotel continued to cater for guests and for special functions including weddings. The 79-year-old General Maczek, Madame Maczek and their daughter became regular summer guests using a room made available to them in the family accommodation. Their visits continued throughout the decade. Those who knew and respected the old general would line up outside in respect as the Maczeks arrived and left.

Enter Klimaszewsky

In the late 1960s and early 1970s Poland was changing. A new effort to emphasise the permanence of Polish land and culture was gathering strength as the Communist authorities struggled to hold on to political control in the face of popular unrest and the challenge of the Catholic Church. A key individual in this effort to steady the ship and secure the status quo in the long term was the geographer Mieczysław Klimaszewski.

A pre-war academic hero, glaciologist and geomorphologist, Klimaszewski (26 June 1908 – 27 November 1995) took part in Poland’s 1938 expedition to Spitzbergen in Norway’s Arctic territory. In 1949 he was appointed to a professorship and, from 1952 onwards, headed the Institute of Geography at the Jagellonian University of Krakow. As head of the University from 1964 onwards he became a vice-regal figure in his rectorial ermine.

In June 1965, Klimaszewski was elected to the Polish Council of State and helped organise the Polish Congress of Culture in Krakow in September the following year. By 1967 he had become deputy-president of Poland and chaired the Supreme Council for the Polish Diaspora (‘Polonia’), reaching out to Polish communities around the world.

Klimaszewski was also chairman of the Tatra National Park and in the 1970s began work supervising a vast Atlas documenting all aspects of the natural and human geography of the region, including its potential for tourism. Kasimierz Trafas was put in charge of the Atlas project, drawing on academic and scientific support and experts from the Military Mapping Institute, the same body which had continued its work in Edinburgh during the war.

In 1973, after the 81-year-old General Maczek and his family had spent another summer break in the hotel, Jan Tomasik met Klimaszewski at a Polonia diaspora congress held in Poland that autumn. The World Polonia Games – Poland’s equivalent of the British Commonwealth Games – were being planned for Kraków in 1974, following a 40-year hiatus since their inauguration in Warsaw in 1934. It was during this visit that Tomasik and Klimaszewski started to discuss building the great Map of Scotland at Barony Castle. The creation of a huge relief map of Scotland in the open air at his hotel at Eddleston would have been perceived by Jan Tomasik as a potential tourist magnet. Klimaszewski’s trusted geographers in Krakow, Kazimierz Trafas and Roman Wolnik, were put in the picture.

Building the Map

In the summer of 1974 General Maczek and his family spent their usual summer break at the hotel. Commissioned by Jan Tomasik, the young Polish geographers from Krakow made their first visit to Scotland. After touring the Highlands to learn more about Scotland’s landscape, they began building the map at Barony Castle by removing topsoil and marking on ground the outlines of the mainland and islands. Then they experimented with cementing and building up the body of the map in the Mull of Galloway and Borders regions. After their return to Poland the work was broken off for another year.

It is worth noting that when the great Map of Scotland came to be built in the mid-1970s, maps and relief models were also at the forefront of government planning in Scotland. It was a time of big ideas. The Scottish Office moved early in 1975 to New St Andrews House, a purpose-built office complex in the heart of central Edinburgh with a well-equipped maps room at the very heart of the building, serviced by a full complement of cartographic, modelmaking and aerial photography interpretation staff.

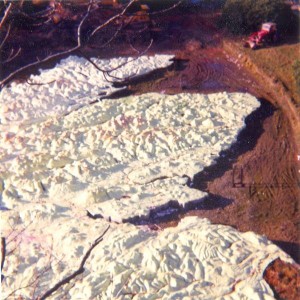

The summer of 1975 saw the Polish geographers return to Scotland, this time accompanied by three hired hands, employees of the University of Krakow under contract to Tomasik for several weeks. The work was supervised by Tomasik’s son-in-law Marek Raton, who took on the role of project manager, assisted by estate farmer and general handyman Bill Robson. Additional labour was supplied by three or four Polish exchange students visiting Britain who had heard about the work at Eddleston by word of mouth. Now aged 83, General Maczek and his family spent their usual summer break at the hotel. With the sale of Learmonth Hotels, the hotel at Black Barony began to operate as an independent business under Tomasik’s ownership. The third visit of Trafas and Wolnik came in 1976. Again, with the help of hotel staff, family members and Polish students, the cement topography was finally completed over a previously laid armature and the finished map painted with undercoat.

When Trafas and Wolnik came to lay out the great Map of Scotland, a scale of 1:10,000 and a x5 vertical exaggeration were selected in line with the standards adopted by the Allies for relief models during the war. These standards were routinely adopted to show general topography, main roads, railways, towns, wooded areas and waterways for use in strategic planning by General Staffs at Force or Army Group level. After the 1976 visit work on the great Map of Scotland slowed down and was done intermittently thereafter. General Maczek and his family continued to spend their annual summer breaks at the hotel. Trafas and Wolnik visited for the last time in 1977 and added some finishing touches to their work.

courtesy of http://www.peebles-theroyalburgh.info/great-polish-map-of-scotland

By 1979 the great Map of Scotland was finally completed with the finishing of the surrounding wall forming the basin. The earth previously excavated to level the ground was banked up outside it. The concrete surface of the map was coated with a plastic resin. Forested areas were painted green, major cities outlined in light brown, major roads and roads through cities painted red, and rivers and lochs blue. Lochs and major rivers had water running through them supplied by gravity through over 40 headwater distributors. (Traces of green and brown paints visible on the map today date from a light surface refurbishment carried out much later.) Even by this time, however, the paint and cement were beginning to show early signs of deterioration.

An End and a New Beginning

In 1979 Catherine and Marek Raton left the hotel, and by 1981 Jan Tomasik’s declining health was sadly slowing him down. Jan Tomasik senior retired in 1981 but the hotel and estate remained with the family. His son, Jan Tomasik junior, had been manager of Learmonth’s International Hotel in Edinburgh, general manager of Unicorn Leisure, including the Glasgow Apollo Theatre, and part of the team operating Radio Clyde.

The hotel closed in 1985, but in the following year Jan Tomasik junior attempted to reconstruct the business. In 1987 he proposed major new investment under the Business Expansion Scheme. In this he was backed by the Birmingham financiers, Centreway, with loans from bankers Hill Samuel & Co and Tennent Caledonian Breweries. Professional advice came from company solicitors Bird, Semple, Fyffe, Ireland and architects Dick Peddie & McKay. Morrison Construction were the managing contractors. The prospectus for the share issue included a plan of the grounds and the words: “A feature of the gardens is a rare, if not unique, relief map of Scotland with waterways.”

Joining Jan Tomasik junior in the directorship were Andrew Harvey of Lismor Records, Norman Quirk, formerly of Radio Clyde, as Financial Director, and Brigadier Keith Hudson CBE, Director of the British Institute of Innkeeping and a former Director of the Army Catering Corps and its Commandant till 1985. The business was renamed the Black Barony Hotel.

In the end, although the hotel interior was demolished and rebuilt, and some extensions were added, the company was unsuccessful in achieving its aims; and by 1990 the Tomasik family’s association of the property had ceased. It then passed through various hands and some of the estate was sold off. For a period it became the main training centre of the Scottish Ambulance Service until it returned to operating fully as a hotel.

The now decaying great Map of Scotland continued to dominate the South Lawn. It was featured in an article in ‘The Sun’ newspaper in 1992. Heather Lowrie reported: “James Paton isn’t kidding when he tells guests they can see the whole of Scotland from the back of his hotel. The 157 ft long, 131 ft wide replica, complete with hills and glens, has well and truly put the country on the map. The masterpiece includes a 5 ft high model of Ben Nevis – plus a [model] train running between Glasgow and Edinburgh. James said: ‘Sam and his friends deserve the recognition for getting it back in shape. It’s all made of old tin cans, chicken wire and things, then covered in cement. It even has rivers and waterfalls.’

The map had clearly been lightly refurbished by the time of this article, possibly with a coat of pale green paint, traces of which can still be seen today. Not long afterwards, the map, complete with a miniature locomotive and track, was spruced up by The Scottish Office so that it could be filmed to illustrate the reorganisation of local government in 1995. Later, when Barony Castle had come into the hands of the Verde group, later De Vere, a further refurbishment was proposed, this time supported by the Edinburgh-based mutual Scottish Widows Fund. But the Fund then became part of Lloyds TSB and the idea was dropped. The current campaign to restore ‘The Great Polish Map of Scotland’ and promote greater recognition of the role of Polish Forces in Scotland during the Second World War began in 2008 with an exhibition in Penicuik Town Hall. The voluntary restoration group Mapa Scotland was formally constituted in May 2010. In the same month, the map was featured on election night with onsite interviews by Lisa Summers for BBC Scotland’s national evening news bulletin.

In September 2012 the Mapa Scotland group secured Heritage Lottery funding for the map’s restoration, as well as listing by Historic Scotland in recognition of the map’s contribution to the nation’s built heritage. It was the subject of a debate in the Scottish Parliament on 19 September 2012 led by Christine Grahame MSP in which its unique importance was recognised. It was warmly commended as a symbol of Poland’s long-standing connections with Scotland up to the present day and a focus for remembering in particular the role of the Polish community in Scotland during and since the Second World War.